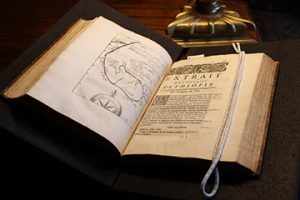

In 1688, Jean Olry, a Frenchman living in Martinique, savoured pineapple for the first time—a rare luxury for Europeans in the seventeenth century. Two years later, while writing his autobiographical account, he vividly recalled the pineapple’s exquisite appearance, declaring it “the most beautiful fruit in all the Indies…[and] indeed, the whole earth.” He also fondly remembered the fruit’s distinctive taste, describing how “it gives off a scent of raspberries and strawberries” and “pleasingly tickles the palate.”. Olry concludes his description of pineapples with a cautionary note, warning that “if you eat it excessively, you will feel ill.”

In spite of what might be imagined given the above passage, with its exoticizing tone reminiscent of contemporary travel accounts penned by adventurers and settlers, Olry was not your typical colonial visitor to Martinique. He had not sought to make a new life on the island. Rather, he had been forcibly deported by the French state, as punishment for his profession of the then-proscribed Protestant religion. The extraordinarily rich personal accounts crafted by French Protestant deportees to the Caribbean, like Olry, torn between pious religious narratives and rather more sensuous tropes of travel writing, offer invaluable insights into the lived experience of intercultural encounter and subordination in the early modern Caribbean.

In spite of what might be imagined given the above passage, with its exoticizing tone reminiscent of contemporary travel accounts penned by adventurers and settlers, Olry was not your typical colonial visitor to Martinique. He had not sought to make a new life on the island. Rather, he had been forcibly deported by the French state, as punishment for his profession of the then-proscribed Protestant religion. The extraordinarily rich personal accounts crafted by French Protestant deportees to the Caribbean, like Olry, torn between pious religious narratives and rather more sensuous tropes of travel writing, offer invaluable insights into the lived experience of intercultural encounter and subordination in the early modern Caribbean.

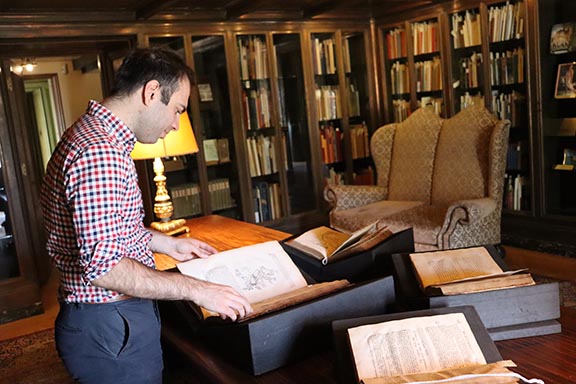

At the recent Core Program Conference “Early Global Caribbean: Conference 2: Convictions” held at the Clark Library in February 2025, I had the opportunity to present my preliminary research into this exciting topic area. Other stimulating contributions included the reflections of Professor José R. Oliver (University College London) on the ethnogenesis of cultural groupings such as the “Taino” and “Kalinago,”, and Professor Owen Stanwood’s (Boston College) investigation of Huguenots’ colonial endeavours in sixteenth-century Florida. It was a real privilege to engage with these presentations, which have deeply enriched my understanding of the various ways power was deployed and experienced in early modern Caribbean space, and will undoubtedly shape the development of my research going forward.

At the recent Core Program Conference “Early Global Caribbean: Conference 2: Convictions” held at the Clark Library in February 2025, I had the opportunity to present my preliminary research into this exciting topic area. Other stimulating contributions included the reflections of Professor José R. Oliver (University College London) on the ethnogenesis of cultural groupings such as the “Taino” and “Kalinago,”, and Professor Owen Stanwood’s (Boston College) investigation of Huguenots’ colonial endeavours in sixteenth-century Florida. It was a real privilege to engage with these presentations, which have deeply enriched my understanding of the various ways power was deployed and experienced in early modern Caribbean space, and will undoubtedly shape the development of my research going forward.

-Dan Rafiqi, 2024–25 Ahmanson Getty Fellow