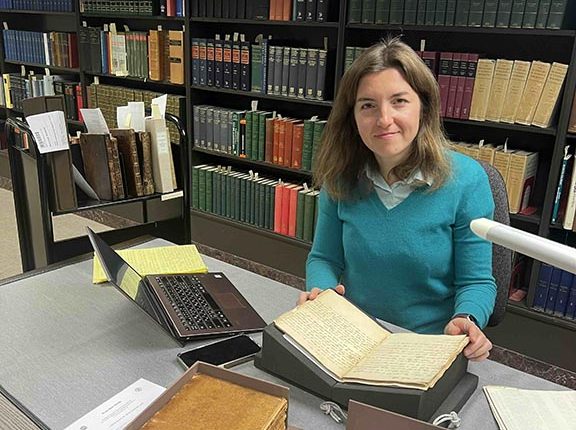

During my time as a Fellow at the Clark Library, I focused on watermarks in early modern cookbooks, exploring how they can provide valuable insights and add new layers of meaning to our interpretation of manuscript culture. While working with the recipe books, I examined the collection of household manuscripts (MS.2016.009), which originated from a wealthy and ancient family in Norfolk.

Acquired in 2016, the manuscript archive, consisting of three bound volumes and one unbound volume, became part of the extensive collection of culinary manuscripts at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. Three quartos still bound in original sheep binding were mainly authored by Elizabeth Berney, the wife of Thomas Berney. The first volume, titled Confectionary Receipts, which is of the greatest interest to me, was compiled around 1785, as evidenced by dates written in her own hand after recipes, such as “Kingsthorpe, Dec.r 19th, 1785” (p. 59).

Despite being well-documented, nothing is known about the possible contributors to the unbound volume. It is undoubtedly older than the rest of the collection, as it is made from paper bearing the Maid of Dort version of the Pro Patria watermark. In contrast, the volume containing confectionary recipes features Britannia and R. Williams watermarks, the latter belonging to a British papermaker active from 1776 to 1789.

Another clue to the age of the unbound manuscript was the selection of recipes, which felt outdated by the late eighteenth century. Recipes such as “Leach,” “Gooseberry Fool,” and “Clear Cakes” all originated from the late seventeenth century to the first third of the eighteenth century. Considering the use of the Maid of Dort watermark, typical of the period circa 1700–1740, and the character of the recipes, I estimated the manuscript’s most probable date to be the 1710s–1720s.

One particular recipe helped me establish a more precise date, at least for the entries made by the first hand. I discovered that the recipe titled “An Admirable Tincture for a Green Wound” was taken from Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, or Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion (p. 199), first published in 1727. This suggests that the collection was likely started in the late 1720s. The inclusion of this recipe was probably prompted by the novelty of the published book, as it is one of the very few purely medicinal recipes in the collection.

One particular recipe helped me establish a more precise date, at least for the entries made by the first hand. I discovered that the recipe titled “An Admirable Tincture for a Green Wound” was taken from Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, or Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion (p. 199), first published in 1727. This suggests that the collection was likely started in the late 1720s. The inclusion of this recipe was probably prompted by the novelty of the published book, as it is one of the very few purely medicinal recipes in the collection.

Knowing the possible date of the manuscript’s origin, I could revisit the Berney family history to identify potential contributors.Moreover, the recipe “To Make Baulm Wine” was attributed to a “cousin Suckling,” which was another hint to one of the original authors. If we go back to the Berneys’ extensive family tree, we will see that in 1700 Thomas Berney (1674 – 1720) married Anne Suckling (1680 – 1743), the daughter of Robert Suckling of Woodton Hall, Norfolk. The unbound manuscript was written by at least four different hands. Despite slight differences, it appears that Anne Suckling was the primary and most significant contributor.

There are other enigmatic aspects of both the unbound volume and the later Confectionary Receipts, which I plan to research and present my findings in an upcoming publication. Overall, the collection of early modern manuscript cookbooks at the Clark Library is a unique and rich resource for understanding not only culinary history but also the transmission of knowledge and its gendered dimensions in the early modern world. And I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to explore this collection with the support of the Bibliographic Fellowship.

-Stefaniia Demchuk, Bibliography Fellow