Core Program

2025–26 | Strange Synchronicities and Familiar Parallels in Asia, 1600–1800: Joseph Fletcher’s Plane Ride Revisited

Organized by Choon Hwee Koh (History, UCLA), Meng Zhang (History, UCLA), and Abhishek Kaicker (History, UC Berkeley)

Co-sponsored by the UCLA Program on Central Asia, Center for Near Eastern Studies, and Center for Chinese Studies

In the 1970s, polyglot Sinologist and Inner Asian specialist Joseph Fletcher had a powerful insight: there were both “interconnections” and “parallels” across the early modern world. Despite Fletcher’s untimely death in 1984, his insight of “interconnections” captured the imagination of a generation of historians who went on to craft histories that were “connected” or, even, “global.” These histories highlighted the myriad kinds of “interconnections” that had forged early modernity.

With this overwhelming attention to “connections,” Fletcher’s second notion of “parallels” came to be relatively neglected. Comparative history, with its profound methodological challenges regarding unit, scale, and criteria of comparison, came to be passed over in favor of the agenda and paradigm of “connected history.” This relative neglect of comparative history has restricted our understanding of the early modern world, in which strange synchronicities and familiar parallels appear across disparate world-regions that were yet to be violently incorporated into a modern global order centered on Europe.

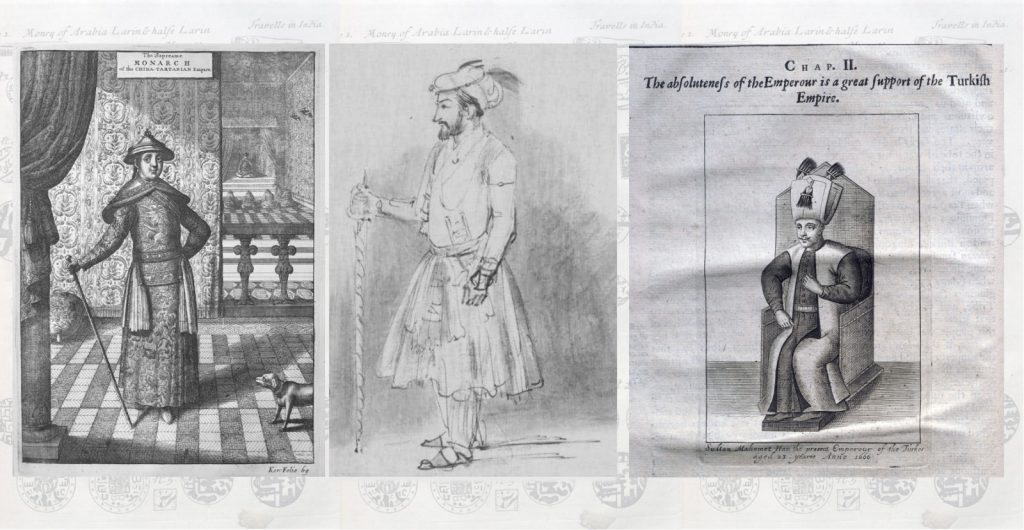

In this cycle of three conferences, historians of the Ottoman, Qing, and Mughal empires return to the problem of comparison by considering synchronicities and structural parallels across Asia. We focus on three broad areas: Imperial Ideology (Empires of Thought), Imperial Operations (Empires in Practice), and Society, Materiality, and Knowledge (Empires of Things).

Early modern empires confronted many similar problems: the ideological and administrative problems of managing diversity, the informational and fiscal problems caused by distance, the centrifugal and centripetal tensions of power, and the delineation and co-optation of status groups, to name a few. The many different solutions that had developed in different regions also shared some striking similarities in their underlying logic. In jointly exploring such differences and commonalities across early modern Eurasia, we aim to devise fresh methodological approaches to tackle old comparative questions in new ways.

Conference 1: Empires of Thought

December 5, 2025

The first conference looks at Imperial Ideology. How did early modern Eurasian empires conceive of and construct power and legitimacy? What were the bases of imperial ideologies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and who were their audiences? More fundamentally, what do we mean when we talk about Eurasian “empires”?

This conference challenges and broadens the default understanding of empire as a large territorial state by focusing on how each empire upheld a normative universe within which particular kinds of political authority and legitimacy were articulated. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Ottomans and Mughals articulated ideas of universal sovereignty in millenarian terms that responded to and co-opted their subjects’ anxieties about the hijri millennium (1000AH / 1591-2 CE). Qing universal sovereignty was constructed as rulership simultaneously rooted in Confucian, Tibetan Buddhist, Islamic, and Shamanistic traditions and surpassing ethno-cultural differences. Rather than assuming a commonality in the aims of historical empires, we seek to understand how varying traditions of thought about power patterned the practices of rule.

Our prompt to participants of the first conference: What might sovereignty mean beyond the political context in which that idea was developed? How did actors conceive of the political order they were constructing, and how did such visions shape and constrain the particular forms of power and legitimacy? How did different visions of political order in turn shape different identifications of potential sources of threats, priorities of rule, and what was acceptable, or even conceivable, as viable policy options?

Conference 2: Empires in Practice

March 6, 2026

The second conference looks at Imperial Operations. How did empires work? What did the mundane, everyday operations of imperial rule look like? Early modern empires confronted the same “great enemy” of distance which severely constrained all actions, from government communications to tax collection. The solutions that the Ottomans, Mughals, and the Qing developed to address these common problems shared some essential features despite their local variations. For imperial communications, each empire had their version of a relay postal system that relied on horses, human-runners, or a combination of both. For the problem of tax collection, each empire distributed tax farming privileges across extensive networks of local intermediaries. Scholars have suggested that empires devised comparable systems of delegating authority and distributing tasks that had more organizational sophistication than previously recognized. Given that such systems of communication and tax collection were apparently autonomously developed in each empire, it is remarkable that these institutional solutions came to acquire significant resemblances with each other. Investigations into these and other areas of imperial operations will lay the foundation for a conceptual framework that might account for both their commonalities and differences and work equally well for these different regions without presuming one type of institutional response as being a universal ideal.

Our prompt to participants of the second conference: How did administrative, tax, or legal innovation overcome the problems of imperial consolidation in the empire of your study? How did they change in this time period compared to previous eras? Is there a particular imperial operation that you have examined in this time period? (This could be a process of resource extraction, of recruiting or managing personnel, of integrating ethno-religious minorities, of instituting new laws, etc.) Is there a question you have for experts of other empires on how this same imperial operation worked there? How might that knowledge help you better understand the empire of your focus?

Conference 3: Empires of Things

May 8, 2026

The third conference looks at Society, Materiality, and Knowledge. In Fletcher’s terms, a “quickening tempo” of increased mobility and commercial activity across the early modern Eurasian space heightened imperial concerns about the effectiveness of political control over increasingly assertive and unruly subjects. Since Fletcher’s work, scholars have discerned a new momentum in cultural production driven by emerging anxieties over a changing social and economic order. These fears were reflected in literature, in legal codes that tried to reinforce status hierarchies, and in new modes of religiosity and spiritual movements. In what new ways did merchants trade, how did artisans and craftsmen organize themselves, how did guilds transform, how did the pious communicate with each other, how did common subjects live, how did spatial imaginaries change?

Whereas the first two conferences largely assume the position and spatiality of the empire, this conference follows the currents of social, material, and knowledge movements across a local, communal, oceanic, or trans-imperial space that might have propelled, supplemented, paralleled, superseded, or completely ignored the agenda of the empire. Rather than assuming a dichotomy of state and society as the norm, we are interested in exploring different modes of mutual interactions in various arenas of power.

Our prompt to participants of the third conference: What social processes or social patterns that emerged in this period had enduring consequences across space and/or time? Is there a material artifact that captures, in your analysis, a defining characteristic of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the empire you study? Is there a mode of knowledge production that captures the particularity of these two centuries in the empire you study?

Composite image: Montanus, Arnoldus. 1671. Atlas Chinensis: Being a Second Part of a Relation of Remarkable Passages in Two Embassies from the East-India Company of the United Provinces… Translated by John Ogilby. London. | Rycaut, Paul, Richard Knolles, Robert White, Frederick Hendrick van Hove, John Macock, and John Starkey. 1680. The History of the Turkish Empire from the Year 1623 to the Year 1677… London. | Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste, and François Bernier. 1688. Collections of Travels through Turky into Persia, and the East-Indies. Giving an Account of the State of Those Countries… Translated by J. Philips and Edmund Everard. London. | Rembrandt, Two Mughal noblemen (Shah Jahan and Dara Shikoh), 1656, pen and wash on paper, The British Museum, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. All other images courtesy of the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, with special thanks to Arie Nair, Reading Room Assistant and Ph.D. Candidate, University of California, Los Angeles.

2024–25 | Early Global Caribbean

Organized by Carla Gardina Pestana (History, UCLA) and Gabriel de Avilez Rocha (Brown University)

Co-sponsored by the Joyce Appleby Endowed Chair of America in the World

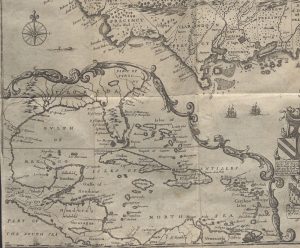

The Caribbean has been a site of global interaction and dramatic change for centuries. Although consideration of the impact of the forces of globalization on the region often focuses on the eighteenth-and-nineteenth-centuries era of sugar and slaves, Caribbean people’s engagement with those forces long predates the period of the plantation complex. Yet a concerted reckoning with earlier global dimensions of Caribbean history, especially one that considers recent advances in scholarly understandings of Indigenous and early colonial histories of the region, has yet to be accomplished. This cycle of conferences and events will serve as an important catalyst for inter-disciplinary dialogue that will move Caribbean studies towards centering transformations in the region’s societies, cultures, ideas, and environments during a period that is conventionally assumed to be prefatory to the histories that followed in its wake.

Conference 1: Convergences

October 18–19, 2024

The Caribbean became global through successive aggregations of disparate peoples across a wide span of time. Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Caribbean Sea served as a bridge among the more than 700 islands that dot the area. For millennia, Indigenous people moved among islands and between them and the adjacent mainland, motived by settlement, trade, and conflict. The circulation of peoples accelerated with the advent of Europeans who seized lands, killed many residents, displaced others, and facilitated the transshipment into the region of scores of enslaved Africans. Black Diasporic individuals would themselves follow routes that introduced new cohesion and terrains of struggle to the region. This meeting will consider the historical constructions of Caribbean space, the waves of people who moved through it across different temporalities before 1700, and the results—both violent and otherwise—that followed these contacts.

Conference 2: Convictions

February 21–22, 2025

The diverse peoples who converged on the Caribbean before 1700 held a range of differing beliefs, ideas about the natural world, and understandings of social, political, and spiritual order. Considering how Indigenous, African, and European systems of thought and faith clashed, adapted, and transformed will be the focus of this second meeting. We invite participants to consider how culturally specific systems of knowledge were expressed and transformed under emergent rubrics of what would become known as religion, science, and law. We will likewise reflect on how these ideas animated the creation and maintenance of institutions of governance and knowledge production both in the Caribbean and extending beyond it. This conference grants an opportunity to weigh how the globalization of the early Caribbean marked historical changes in beliefs and ideas but also witnessed continuities that cut across the 1492 divide. In the process, a multitude of convictions about spiritual, natural, corporal, social and political order helped shape (and were reshaped by) encounters in the Basin.

Conference 3: Materialities

April 11–12, 2025

The tangible realities of daily life and the patterns of exchange in the Caribbean and the other Atlantic regions integrated into the Caribbean’s orbit enhance our understanding of the local dimensions of global processes that have long shaped the Caribbean Basin. This final conference will consider how the region’s early global histories may be tracked through their material manifestations in constructed and natural environments from a variety of different disciplinary perspectives. Focusing on the materials embedded and moving through Caribbean land- and waterscapes prompts lines of investigation about how historical interactions and social constructions of meaning were mediated across different historical moments. These interactions and constructions can be explored through physical artifacts, objects, and living organisms. We will deliberate on how both the environment itself and the material cultural productions of the people living in the Basin were profoundly and continuously influenced by the advent of different groups, the imposition of new agricultural regimes, and a host of other aspects of quotidian life that persisted, gained new forms, or disappeared. To what extent might the historical study of transformations in the circumstances of life in the Caribbean benefit from considering distributed agencies of different human and non-human actors across time? What do considerations of materiality in or beyond traditional archives contribute to a global understanding of Caribbean history?