Date/Time

Wednesday, May 5, 2021

9:30 am PDT – 12:00 pm PDT

Wednesday, May 5, 2021

9:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m. PDT

Zoom Meeting

–Organized by Vin Nardizzi, The University of British Columbia, and Bronwen Wilson, University of California, Los Angeles

Co-sponsored by University of California Humanities Research Institute

This symposium is one outcome of a UBC and UCLA Collaborative Research Mobility Award. Its long-time collaborators, Dr. Vin Nardizzi (English, UBC) and Dr. Bronwen Wilson (Art History, UCLA), are key researchers in the international collaborative project “Earth, Sea, Sky”. Wilson is also one of three principal investigators in the UCHRI project: On the sea and coastal ecologies: early modern pasts and uncertain futures. We are grateful to our collaborators and these institutions for their support.

Chair: Vin Nardizzi is Associate Professor in the Department of English Language and Literatures at UBC. With Tiffany Jo Werth, he recently edited Premodern Ecologies in the Modern Literary Imagination (Toronto 2019), and he is completing a book manuscript called “Marvellous Vegetables: Plants and Poetry in the English Renaissance.”

Moderator: Laura Hutchingame, Graduate Student, Art History, UCLA

Robert N. Watson is Distinguished Professor of English at UCLA. He is the author of Back to Nature: The Green and the Real in the Late Renaissance (2006). His most recent monograph, 2019, is Cultural Evolution and its Discontents: Cognitive Overload, Parasitic Cultures, and the Humanistic Cure.

Ayasha Guerin is Assistant Professor of Black Diaspora Studies, Department of English, UBC. Her presentation springs from a book project, which argues that the waterfront has served the frontlines of crisis for racialized communities since European colonization and trans-Atlantic slave trade. A related article, “Shared Routes of Mammalian Kinship: Race and Migration in Long Island Whaling Diasporas,” is forthcoming in Island Studies Journal.

Joseph Monteyne is Associate Professor, History of Art, at UBC. His forthcoming book is Media Critique in the Age of Gillray: Scratches, Scraps, and Spectres (University of Toronto Press, late 2021, early 2022).

Bronwen Wilson teaches art history at UCLA where she is Director of the Center for 17th- and 18th Studies and the Clark Library. Her new book project, Otherworldly Natures: the subterranean imminence of stone, probes artistic and ecological engagement with quarries, riverbeds, and lithic formations from the middle of the fifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth.

Schedule

9:30 a.m.

Opening remarks, Vin Nardizzi

9:35 a.m.

Robert N. Watson, University of California, Los Angeles

“Donne on the Shore”

9:50 a.m.

Ayasha Guerin, The University of British Columbia

“Echolocation, Race and Migration”

10:05 a.m.

Discussion

10:25 a.m.

Graduate Student Presentations

Nicolyna Enriquez, University of California, Los Angeles

“Surrounded by Sea: Graffiti and Ship Imagery on Cretan Church Wall Paintings”

Abigail Berry, University of California, Los Angeles

“Fluid Boundaries of the Invisible: Quarantine in Fifteenth-Century Europe”

Cynthia Fang, University of California, Los Angeles

“Imaginary Voyages: a Sailing Ship at the Aviary in Yuanming Yuan”

10:45 a.m.

Discussion

11:00 a.m.

Break

11:10 a.m.

Bronwen Wilson, University of California, Los Angeles

“The Sea, the Line, and the Limits of Perspective”

11:25 a.m.

Joseph Monteyne, The University of British Columbia

“Equivocal Space and the Problem of the Sea in Blake and Fuseli’s Images of Dante’s Cocytus”

11:40 a.m.

Discussion

12:00 p.m.

Program concludes

Abstracts

Robert N. Watson, University of California, Los Angeles

“Donne on the Shore”

For the 17th century poet and preacher John Donne, as for many sailors of his day, the coastline was frequently a matter of life and death. Donne famously wrote that “no man is an island.” My argument is that Donne perceived every person as a shoreline, always at risk — from tempest or just from the tides of time — of becoming reduced to “a clod…washed away by the sea” to death.

Donne persistently associated the passage from land to sea with the passage from life to death. The key question, as Donne moved from his egotistic sensualist love-poems to his religious hymns, was whether to understand the departure from land as drowning and oblivion, or instead as a baptismal ablution preparing him for salvation. Stepping off a dock entailed a leap of faith, a non-rational trust that a meaningful immortality of something like his fiercely-guarded self would survive in that cold, swirling ocean.

For Donne and other writers of the period in that island nation (such as Shakespeare and Lovelace), land was perceived as a stable human habitation, while oceans epitomized the chaotic churn of matter and motion that the revival of classical skepticism and atomism had made uncomfortably evident to many Renaissance thinkers.

Donne’s “Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” with its renowned conceit of parting lovers as the legs of a draftsman’s compass, struggles with departure-anxiety and strives to insist that – by the power of will and intellect, in both of which Donne knew himself strong – he still retains a foot on the land even after his ship’s departure, which the poem begins by equating with death itself. Another of his valedictions, “Of Weeping,” pleads with his weeping lover to forbear “To teach the sea what it may do too soon.”

The “Hymn to God the Father” confesses to a “sin of fear, that when I have spun / My last thread, I shall perish on the shore.” In the Holy Sonnet “If Poisonous Minerals,” in the “Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness” and in the “Hymn to Christ at the Author’s Last Going into Germany,” Donne strives to transforms his terror of drowning into a hope of a cleansing that will prepare him for blissful immortality instead of mere annihilation. That struggle persists in the direly ailing Donne’s Devotions on Emergent Occasions, and in a Whitsunday sermon, and right up through the ambivalent emblem he chose on his death-bed: Christ, not on a cross, but on an anchor.

Whether the oceans, as they rise to erase our lands, will hold our redemption or our condemnation seems a question no less urgent that it was four centuries ago.

Ayasha Guerin, The University of British Columbia

“Echolocation, Race and Migration”

This paper begins with acknowledgement of the coastal Algonquian people of Long Island, New York, and their changing relationship to whales under colonial capitalist policies. Before the discovery of petroleum in the mid 19th century, oil extracted from the blubber of sperm and right whales was used to light the lamps of North America and much of the Western world. For over two hundred years of coastal, colonial settlement, New England served as epicenter of the whaling industry. While many whalers were also of European descent, this work centers the lives of Black and Indigenous people and their relationships with whales to analyze how colonial impositions of racial differences have instigated new assemblages of oceanic social life.

Algonquian people on Long Island’s waterfront provided the first muscle for the growing industry. Whaling work brought Indigenous New Yorkers into relationships with European and African whalers. The number of Black whalers in the industry grew over three centuries with enslaved Africans, and by the hire of free Black fugitives and recruitment of African islanders from Cape Verde and other colonial ports. As skilled hunters, swimmers, and navigators, Indigenous and Black people were disproportionately represented in New England’s early whaling ventures, but their opportunities for advancement were compromised by the introduction of racially discriminatory laws and practices that trapped them into spirals of debt while whale populations were depleted. By the end of the 19th century, American whaling voyages stretched several years across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, their risky pursuits accelerated to satiate the desires of a globalizing world hooked on oil.

And whales were not passive actors — they fought back and took human casualties with them. Whales are also very intelligent; they move when heavily attacked in one area. Marine biologists believe that whales communicate with one another through a process of echolocation: active sonar which registers to the human ear as a variety of clicking sounds. As whaling was industrialized, whales responded using echolocation’s clicking codes to help them sense and register large moving targets and danger ahead, and to develop new routes of navigation. The farther the fisheries had to travel from local shores to find whales to kill, the more dangerous the journeys were for whalers.

In showing how intimate relations between whales and whalers were shaped by processes of colonization, coastal displacement, and by conditions of indebtedness, enslavement, and fugitivity, I reveal the entangled fates of species under colonial capitalism and the value of cultivating mammalian kinship for our shared survival. Demonstrating how the extractive conquests of colonial settlers shaped the exploitative treatment of whales and the movements of social groups who lived in dependence to them, I build on Black feminists’ theoretical work and methodologies to look for interspecies, trans-oceanic navigations of survival. I argue the importance of recognizing whales as mammalian kin, caught in the same net of colonial capitalist settlement and resource extraction as their hunters. Finally, inspired by the metaphor of echolocation, a method of listening which helps whales to navigate oceans, I suggest that we might listen for the socio-ecological reverberations of historic whaling diasporas to learn emergent strategies of survival.

Bronwen Wilson, University of California, Los Angeles

“The Sea, the Line, and the Limits of Perspective”

The subject matter, Submersion of Pharoah in the Red Sea, became an allegory of the political threat of the League of the Cambrai, when European rulers joined forces to quell Venetian expansion on the mainland. As noted recently, the theme was also an expression of precarious ecological conditions for the Venetian lagoon. Not only flooding but also reduced water levels required on-going management of resources. Titian’s design of the biblical story for an immense woodcut (c. 1515-1520), the focus of my talk, is a startling rumination on divine intervention, elemental turmoil, and human violence.

Shapes of water solicit involvement with the sea that swells across two square meters of the composite woodcut. On the left, water engulfs human and equine bodies, their limbs entangled, as they are subsumed by vigorous cross-hatching. Calligraphic lines are interrupted by the white of the paper where waves crest as they guide us diagonally across manifold sheets toward a rocky outcrop on the right. This rhythmic force vies for our attention with a seemingly infinite vista where the sky meets the sea at the horizon, robustly rendered in a few parallel lines. The forms of the sea are echoed in the sky, which seems to fold back over, as if a canopy, returning us to the foreground where Moses and the Israelites gather.

By exploring the forces of the sea, the woodcut contends with the limits and potential of human artifice. The sea interacts with land and stone, unforming and re-forming its contours. It overflows the limits of the printed image, disrupting the optical operations of perspective, and playing with the corporeality of viewers. Accordingly, the Submersion raises questions about the conversion of time into lines, about the ambivalence of the horizon, and about the limits of what can be seen and known. These pictorial investigations, and their philosophical implications, have relevance for other examples of early modern maritime imagery.

Joseph Monteyne, The University of British Columbia

“Equivocal Space and the Problem of the Sea in Blake and Fuseli’s Images of Dante’s Cocytus”

My paper examines the disorienting perspectives utilized by William Blake and John Henry Fuseli in their illustrations of Dante and Virgil on the frozen body of water known as Cocytus, subject matter taken from their encounter with the Italian poet’s Inferno in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For example, a striking head engraved by William Blake around 1789, based on a design by Fuseli, has long been accepted as depicting one of Dante’s damned figures in hell. The print features the dramatically foreshortened head of a figure who looks up and to the left with opaque, unseeing eyes, his mouth open, and a tortured expression appearing on his face. Usually described as one of Dante’s figures being tortured by the flames of hell, I intend to challenge this assumption by positing that this head is in fact trapped in the ice of Cocytus. If this is the case, the beholder is given a viewpoint from disturbingly close range, claustrophobically positioned beneath this head as if their own body is stuck in the ice underneath, in like manner to those individuals described by Dante as being trapped like pieces of straw in glass. Blake rejects any notion of distance receding into the background in this print and chooses to emphasize the uncomfortable and oppressive physical closeness of the viewer to the figure in order to echo the suppression of sight and the destabilization of figure and ground associated with Cocytus.

I will argue that it is precisely this kind of visual tension that is also found at the center Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s ‘problem of the sea’. As they articulate, prior to ‘striation’, navigation of the ‘smooth’ space of the sea was achieved through the wind, noise, colors, and sounds of the sea, the ‘sonorous and tactile qualities’ also associated with the desert, steppe, and ice. Striation allows the production of distant and optical space, whereas the smooth generates ‘close vision-haptic space’. As with the viewpoint established by Blake’s print, ‘one never sees from a distance in a space of this kind, nor does one see it from a distance’ (Mille Plateaux, 493). Similar tensions, contradictions, and inversions are found in Blake’s other images based on Dante’s Inferno, particularly those commissioned by John Linnell for a proposed publication. In one pencil drawing, for instance, Blake set out to map Dante’s hell in order to conceptualize this large project. Mapping the circles of Dante’s Inferno in cross section was not unusual, and Blake had many visual precedents to draw upon. What is most striking about Blake’s map, is that it stands in opposition to every other map that positions Jerusalem and the surface of the earth near the top of the image, and deploys a series of concentric circles that descend towards an increasingly narrow and constricted Cocytus. Blake inverts this arrangement entirely and positions Satan frozen in Cocytus at the top of the page. In the margin of his sketch Blake writes ‘This is Upside Down’, and defends his claim by stating that in ‘In Equivocal Worlds Up & Down are Equivocal.’ This viewpoint will be a feature of his other drawings of this icy realm.

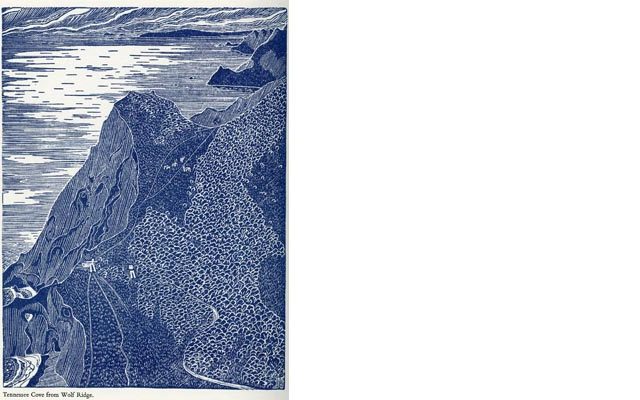

Image: Tom Killion, Tennessee Cove from Wolf Ridge, 1977, in Fortress Marin : An Aesthetic and Historical Description of the Coastal Fortifications of Southern Marin County (Santa Cruz, Quail Press, 1977)