During my month’s residence as a History of Science Fellow at the Clark Library, I was able to conduct archival research to support my doctoral dissertation, “On Vegetables and Vermin: The Politics of Insect-Plant Encounters from the Early Modern to the Anthropocene.” This project foregrounds the ways in which interactions between plants and insects, from pollination and insectivory to parasitism and infestation, intervene in the regulatory schemas that shape human life at specific points in transnational European history. Such insect-plant encounters, I argue – in their creeping, buzzing, stinging, rotting, and blooming materiality, as well as their incarnations in text and visual culture – essentially perform an act of political thinking that makes new modes of thought and relations among bodies both possible and manifest, and give rise to emergent and often unpredictable organising principles for human life along the lines of gender, sexuality, race, and class.

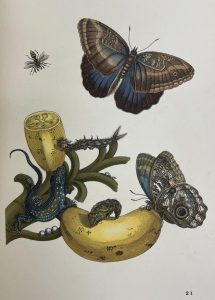

This project is rooted in a study of sixteenth- to eighteenth-century Europe as a time and space in which the relationships among humans, plants, and insects were being actively renegotiated.  It contends, further, that these reconfigurations in early modern thought are crucial to understanding how certain racialised and gendered bodies come to be represented and policed in later contexts such as the rise of empire, industrialization, technopolitics, and the Anthropocene. As such, I spent my time at the Clark researching for two dissertation chapters with an early modern focus. The first, “Spontaneous Generation,” investigates how seventeenth- and eighteenth-century scientific debates about spontaneous generation contribute to the material policing of feminine bodies as sites of disorderliness, pathological contagion, and witch-likeness in early modern Britain, Germany, and Italy. I was able to examine archival texts by the botanical illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian, a pioneering female figure who was among the first to depict insects and plants in their multitudinous ecological entanglements and who argued, daringly, against the doctrine of spontaneous generation. I also consulted materials by the famed microscopist Robert Hookeand the mystic and adventurer Antonia [Antoinette] Bourignon, the lover of microscopist Jan Swammerdam and an accused witch herself. The question of whether Swammerdam’s work on spontaneous generation plays any role in the accusations levied against Bourignon is one of the many mysteries to which this chapter attends

It contends, further, that these reconfigurations in early modern thought are crucial to understanding how certain racialised and gendered bodies come to be represented and policed in later contexts such as the rise of empire, industrialization, technopolitics, and the Anthropocene. As such, I spent my time at the Clark researching for two dissertation chapters with an early modern focus. The first, “Spontaneous Generation,” investigates how seventeenth- and eighteenth-century scientific debates about spontaneous generation contribute to the material policing of feminine bodies as sites of disorderliness, pathological contagion, and witch-likeness in early modern Britain, Germany, and Italy. I was able to examine archival texts by the botanical illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian, a pioneering female figure who was among the first to depict insects and plants in their multitudinous ecological entanglements and who argued, daringly, against the doctrine of spontaneous generation. I also consulted materials by the famed microscopist Robert Hookeand the mystic and adventurer Antonia [Antoinette] Bourignon, the lover of microscopist Jan Swammerdam and an accused witch herself. The question of whether Swammerdam’s work on spontaneous generation plays any role in the accusations levied against Bourignon is one of the many mysteries to which this chapter attends

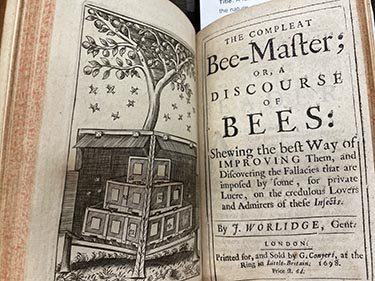

My time at the Clark also proved valuable for the development of my final chapter, “Biomimicry.” This was unexpected, for my research into biomimicry focuses on twenty-first century robotic appropriations of the honeybee – such as Harvard’s RoboBee – that have been engineered to support ailing pollinating insect populations in a time of colony collapse disorder and ecological precarity. My primary interests lie in the interplay between pleasure, artifice, and violence in such technological appropriations of Apis mellifera, and I had originally planned for this chapter to focus on the contemporary moment. However, while consulting materials from the Clark’s archives, I was struck by the terms in which thinkers such as Samuel Purchas (1577-1626) and John Thorley (1671-1759) frame their relationship to the honeybee. They are, of course, admiring of the bees’ social structure, as Western philosophers have been since antiquity. But their esteem for the “excellence” of bees is premised, first and foremost, on the commodities these insects produce for the benefit of mankind, such as sweet honey and versatile wax. It is this production of such highly desirable outputs, both Purchas and Thorley attest, that sets bees apart from even the most interesting, even the rarest of other insects.  It appears feasible to me, then, that the highly anthropocentric attributes for which honeybees have been lauded over the centuries – including their purported loyalty and subordination to a monarch, industriousness, hierarchised division of labour, and a harmonious social structure – emerge first and foremost as a mediation of their capacity to produce pleasure-inducing commodities in cooperation with plant life, from which humankind can profit. This led me to question whether a similar motivating force is at play in twenty-first century calls that rally to “save the bees” by any means possible – including, if necessary, their supplementation with robots. It seems the case that, in the context of the Anthropocene, our proclaimed love and admiration for the honeybee is still premised in the first instance upon what they can afford us in their use-value as capital-intensive livestock, albeit now primarily in the position of profitable migratory pollinators, rather than producers of honey and wax. This led me to the question that now sits at the core of this chapter: what symbolic, ecological, and material-social outcomes does this framing of the honeybee as a producer of commodities – and one that can therefore be replaced, even improved upon, through technological interventions – blind us to?

It appears feasible to me, then, that the highly anthropocentric attributes for which honeybees have been lauded over the centuries – including their purported loyalty and subordination to a monarch, industriousness, hierarchised division of labour, and a harmonious social structure – emerge first and foremost as a mediation of their capacity to produce pleasure-inducing commodities in cooperation with plant life, from which humankind can profit. This led me to question whether a similar motivating force is at play in twenty-first century calls that rally to “save the bees” by any means possible – including, if necessary, their supplementation with robots. It seems the case that, in the context of the Anthropocene, our proclaimed love and admiration for the honeybee is still premised in the first instance upon what they can afford us in their use-value as capital-intensive livestock, albeit now primarily in the position of profitable migratory pollinators, rather than producers of honey and wax. This led me to the question that now sits at the core of this chapter: what symbolic, ecological, and material-social outcomes does this framing of the honeybee as a producer of commodities – and one that can therefore be replaced, even improved upon, through technological interventions – blind us to?

–Daisy Reid, University of Southern California