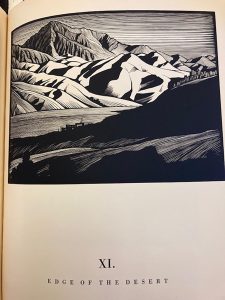

In 1931, wood engraver Paul Landacre published his first major work, California Hills. A transplanted Midwesterner, Landacre had encountered various of the sites depicted—Monterey, Big Sur, Coachella Valley—on a road trip with friends (Landacre did not own an automobile). They followed touring itineraries suggested by the popular Sunset Magazine, a publication sponsored by the Southern Pacific Railway to promote a vision of California as an unspoiled Eden open to development. Landacre’s images have a slightly moderne stylishness to them, embodying his unique approach to rendering form with sculptural conviction, in dramatic high contrast shade and shadow, rather than with the descriptive line-work often typical of engraving. Most of the images are uninhabited landscapes, but also included are the Physics Building at UCLA, the Stadium at UC Berkeley, and one very 1930s streamlined nude whose caption describes her as “sapling slim” in a phrase reminiscent of the era.

Reading these idyllic and idealized images now, in full recognition of the history of the displacement of Indigenous peoples, systematic genocide, erasure—and what Joy Holland, librarian in the American Indian Studies Center describes as Indigenous “persistence” is a challenge. Landacre was borrowing from an established tradition of Romantic landscape that ignored the history of contact, ethnographic documentation, settlement and development though they–appear in the visual record. But Landacre was also a self-identified “naturalist,” and his appreciation and representations of California need to be understood in their own historical moment as well as from our own.

Reading these idyllic and idealized images now, in full recognition of the history of the displacement of Indigenous peoples, systematic genocide, erasure—and what Joy Holland, librarian in the American Indian Studies Center describes as Indigenous “persistence” is a challenge. Landacre was borrowing from an established tradition of Romantic landscape that ignored the history of contact, ethnographic documentation, settlement and development though they–appear in the visual record. But Landacre was also a self-identified “naturalist,” and his appreciation and representations of California need to be understood in their own historical moment as well as from our own.

The Landacre papers and archive at the Clark provide an unusually detailed insight into the social, financial, and personal life of this artist. His career began in the early years of the Depression as Southern California had experienced the boom effect of the discovery of oil, implemented irrigation to promote agriculture, connected with the rest of the state and nation through the railroads, and witnessed the emergence of the Hollywood film industry. Landacre arrived into this burgeoning world in the late 1920s, and his papers show clearly the extent to which his career was linked to the cultural aspirations of a growing elite in Los Angeles. Fine press printing and elegant (but consumable) visual art were conspicuous signs of an emerging local moneyed class who gravitated towards these activities as evidence of their own sophistication. This was the milieu in which the book dealer/gallerist and visionary Jake Zeitlin fostered an intellectual community through his bookstore in Los Angeles, attracting figures like Ward Ritchie and Lawrence Clark Powell, among others who became luminaries in the region.

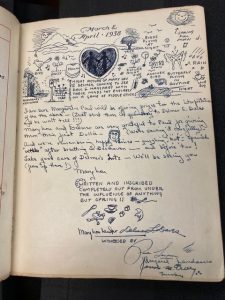

Landacre’s adult life and career are intimately connected to Los Angeles, though his work came to be represented in major museums—MoMA and the Whitney in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the National Gallery in DC to name some of the most prestigious. But that success came later and much of his life was financially precarious with income coming from commissions for book illustrations and some commercial work. He was supported locally by a group organized to supply a subvention, the Paul Landacre Association, individuals who received prints in exchange for a monthly donation. The papers lay bare these explicit details. Every transaction—revenue received and outlays for expenses—is documented in his financial records. Similarly, each communication around a commission or sale, exhibit or engagement, has left a trace in the correspondence. Engraved letterhead stationery, telegrams with their strips of text pasted onto a Western Union form, personal letters with a sketch here and a flourish there, many written in handwriting now too elegant to imitate–all provide a rich material history of a life in a now-vanished moment in time. Landacre’s sketches, photographs, notes for projects, and the hand-carved blocks themselves are also preserved for study. In addition to the actual Landacre materials, the Clark’s holdings offer much with which to contextualize and consider his work. The extensive collections of Los Angeles fine press materials, for instance, put Landacre’s work in dialogue with that of other artists depicting the landscape—such as Seeing California with Edward Weston, 1939, a photographic publication sponsored by an automobile association.

The Ahmanson seminar I taught in Fall 2022 took up the question of Landacre’s Calfornia Hills in relation to the absence of any trace of indigenous presence. For this, other materials in the Clark’s holdings were also relevant—the multiple editions of George Catlin’s Indian Gallery, the Book Club of California publications of views of the region during initial phases of development of the pueblo-presidio-mission system, maps of settlement, and appropriation. Other surprising documents supplement Lanacre’s archive. One is an early edition of Lewis and Clark’s New Travels among the Indians of North America, an 1812 excerpt of earlier “communications already published”. Another is a facsimile of B.D. Wilson’s sympathetic but ignored 1852 Report on The Indians of Southern California, issued on its centenary as a facsimile produced by the Huntington Library. An original 1868 pamphlet from the Montana Collection, Report of the Indian Peace Commissioners, contained a “message from the President of the United States,” Andrew Johnson, as part of an Act of Congress “to establish peace with certain hostile American tribes.” The language, format, and substance of these publications have an overwhelming authenticity to them. Other little-known treasures in the Clark collections, Chiura Obata, From the Sierra to the Sea, 1937, with hand-painted images on each page of the entire edition of fifty copies, Robert H. Vance’s 1946 A Camera in the Gold Rush, H. Bennet Abdy’s Old California printed in San Francisco in 1924 by the prestigious printer, John Henry Nash are just a tiny handful of the many works that provide useful volumes with which to situate Landacre.

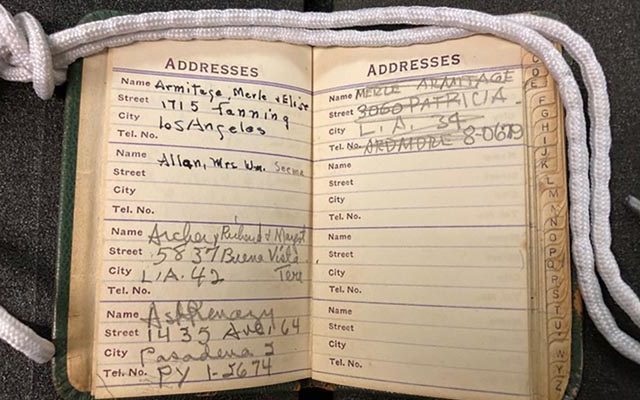

Many online materials, such as the Robert B. Honeyman Collection at the Bancroft in Berkeley, available through the Online Archive of California, contain extensive early ethnographic documentation that add their own dimensions. And extensive secondary material on California history, land management, Indigenous practices and lifeways, including those in the Library of AISC all filled out the resources for the seminar. But the impact of working with the archive, handling Landacre’s papers, looking through his address book, his notebooks, his guest book—this experience has an immediacy unlike any other. The papers also offer a view into the cultural history of Los Angeles in the 1930s-60s through the networks and activities of a gifted artist who flourished in part because of the larger community.

Many online materials, such as the Robert B. Honeyman Collection at the Bancroft in Berkeley, available through the Online Archive of California, contain extensive early ethnographic documentation that add their own dimensions. And extensive secondary material on California history, land management, Indigenous practices and lifeways, including those in the Library of AISC all filled out the resources for the seminar. But the impact of working with the archive, handling Landacre’s papers, looking through his address book, his notebooks, his guest book—this experience has an immediacy unlike any other. The papers also offer a view into the cultural history of Los Angeles in the 1930s-60s through the networks and activities of a gifted artist who flourished in part because of the larger community.

Landacre’s status as an artist remains appropriately modest. His achievements deserve recognition, but the impact of his oeuvre was fairly limited, in part because much of his work was done for book publication and illustration, not as fine art—such as his extensive partnership with the well-known nature writer Donald Culross Peattie. Working with the archive was an opportunity to consider how we encounter and understand the cultural record of an individual figure within the sociology and history of their life and work. The Landacre archive is focused and specific, but multi-faceted, and like much else at the Clark, is a rare, under-utilized, and unique resource for primary research for pedagogy and scholarship.

–Johanna Drucker (Breslauer Professor of Bibliographical Studies in the Department of Information Studies at UCLA)