While the nationalistic myth of Japan as a homogeneous society has persisted, two marginalized groups—the Ainu and the Ryūkyūan—challenge this misconception. This pivotal topic took center stage at the final conference of the Open Edo series, hosted at the UCLA William Andrews Clark Memorial Library on April 19, 2024. Titled “Edo Outsiders: Ainu and Ryūkyūan Art,” the conference marked the culmination of a trilogy of Open Edo conferences that commenced last October, all dedicated to exploring Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868).

The first panel of the conference centered on Ainu material and visual culture in relation to their history, materiality, and practice. Christina M. Spiker delivered a presentation on Ainu woodcarvings, emphasizing their role in representing Ainu identity and their enduring relevance despite their exclusion from mainstream art history narratives. Fuyubi Nakamura discussed the work of contemporary Ainu artist Mayunkiki, who expresses her indigenous identity through sinuye, a traditional tattooing practice for Ainu women. This practice, formerly subjected to government regulation, serves as a manifestation of Ainu culture’s subjectivity. Katsuya Hirano examined the relationship between the Ainu and the Wajin (mainland Japanese people), focusing on their interactions in the kelp trade and shedding light on their intricate mutual dynamics during the Edo period. Subsequent discussion addressed additional issues, including the inclusive or exclusive concept of ‘we’ as an indigenous group or national entity and the classification and status of Ainu artifacts and materials.

The second panel delved into the circulation and dynamism of Ryūkyūan textiles and lacquerware. Setsuko Nitta provided insights into bingata, a Ryūkyūan dyeing technique, and its development in motifs and materials through cross-cultural exchanges, particularly with Japan and China. Monika Bincsik explored the international context of Ryūkyū lacquerware, comparing it with lacquer styles from Korea, China, and Japan. The subsequent discussion extended to the class relationships in aesthetics, the connections between lacquer and textile designs, and the distinctive indigenous features of bingata compared to its Japanese counterpart.

The third panel focused on Ryūkyūan painting, heritage, afterlives, and restorations. Eriko Tomizawa-Kay offered a reinterpretation of Ryūkyūan painting, challenging traditional Japanese art history narratives and illuminating its significance beyond mainland Japan. She underscored its distinct aesthetic and thematic qualities, which reflect both Ryūkyūan culture and influences from overseas. Heeyeun Kang delved into Ryūkyūan royal portraits, known as Ugui, contextualizing them through recently rediscovered artworks. Kang highlighted their self-identity and conducted a comparative analysis with Chinese and Korean counterparts, drawing upon textual and visual evidence. The discussion session addressed issues concerning the perception of Ryūkyū as a maritime country, the unique aspects of Ryūkyūan culture, and the presence of nationalism in Okinawa.

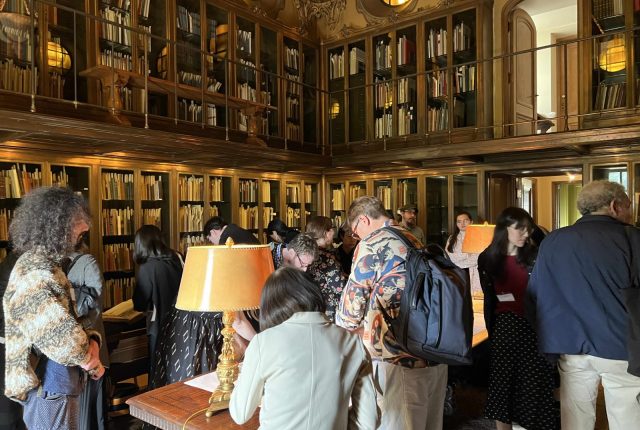

During the lunch break, a special viewing was arranged in the North Book Room, allowing participants to explore Clark Library materials, including Atlas Japannensis (1670) by Arnoldus Montanus (1625–1683). Overall, this conference served as a meaningful forum for discussing marginalized Ainu and Ryūkyūan art and culture. It shed light on their voices, identities, and contexts, offering insights into the frequently overlooked history of Japan’s Edo period. Consequently, the conference effectively showcased the cultural and historical pluralism of early modern Japanese society and art, which is often overshadowed by master narratives.